Original Publication:

Ole Waever, “Securitization and Desecuritization,” in On Security, edited by Ronnie D. Lipschutz (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), pp. 46-86.

My Reference:

Ole Waever, “Securitization and Desecuritization,” in International Security: Widening Security, vol. 3, edited by Barry Buzan and Lene Hansen, 4 vols. (Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2007), 66–99.

[Google Drive Link]

Ole Waever explains securitization in this fantastic video.

This is a very satisfying read, not only but especially, as a conceptual paper. It is refreshing to see references, some explicit others implicit, some central others incidental, to the wider philosophical literature — Wittgenstein, Hobbes, Rousseau, Clausewitz, Austin, and even to Hegel in an important but enigmatic passage.

But of course as a paper addressing a problem in the study of security specifically and international relations more broadly, it not only refers to classics within the field — Morgenthau, Aron — but is responding to a certain development: the increasing push, starting from the 1980s, for widening the reach of security beyond military issues. Some of the texts he is responding to are Barry Buzan’s seminal People, States, and Fear (1983), Richard Ullman’s “Redefining Security” (1983), Johan Galtung’s “Twenty-Five Years of Peace Research” (1985), and Jessica Tuchman Mathews’, “Redefining Security” (1989). See the References/Further Reading for full bibliographic information.

I will summarise, as is my practice, only the conceptual parts and try to comment more fully than Waever on some of the philosophical ideas from which he is drawing.

The advanced reader can skip the comments marked off by a coloured background.

************************************

This is an attempt to to present one perspective on security and to assess its implications in the light of four selected “security agendas”.

I summarise only the perspective on security being offered.

Traditional and even critical, but now established, perspectives on security have been unsatisfactory. Such approaches assume not only that security is something out there, has a reality on its own, or pre-given, but also that the more the security, the better. They also argue that security should cover more than what it currently covers.

Is such a move this desirable? After all, at the heart of security is the defense of the state. And designating something, say environmental issues, as security issues results in the allocation of a significant role to the state, which might not be the best way to approach them. But more crucially, why assume that security is something pre-given?

Security: The Concept and the Word

In the 1980s, there was a general move to broaden the concept of security so that it referred not just to the state but also to people, whether as individuals or indeed as a global collectivity. But individuals can be affected in any number of ways: economic, political, cultural, environmental. Often military issues are far from people’s minds. The problem with this approach at broadening security is that it begins to include everything within its ambit. “How, then, can we get any clear sense of the specific character of security issues, as distinct from other problems that beset the human condition?”

The broadening is at two levels here. First, in terms of the referent (the security of what question): not just the state but also people whether as individuals or as a global collective, or in other words not just national security but also individual and global security. Second, in terms of the threats (the security from what question): not just military threats but also environmental, cultural, economic, social, etc. threats.

Waever’s task will be to make space for diverse threats (like his predecessors) within the concept of security. But he wants to do this with a concept which is not only tied to the state but also does not entail its expansion to any and all issues (both unlike his predecessors). More below.

One way is by narrowing the referent object axis. That’s to say, by resisting the temptation to extend security to more and more objects: i.e. the individual or to the whole world. In the attempts to expand or broaden the notion of security, scholars have merely adopted the traditional perspective/concept of security and applied it to more objects. But because our understanding of concept of security is inevitably tied up with the notion of national security understood in terms of military defense, the extension of this concept to non-traditional realms such as individuals or indeed the whole world is problematic. Let us therefore keep this in mind: the concept of security refers to the state.

This is a complex argument. It is as follows. As a word, security can mean a lot of things. One need only consult a good dictionary. Security used this way is abstract (and useless). But as a concept, security means something and refers to something. It means, roughly, national security, and refers to the state (more below). Security in this sense is analytic(ally useful). [Hence the title of the subsection!]

Now, in the attempts to broaden the notion of security, various other referents apart from the state have been subsumed under security: Waever mentions individuals and the global collectivity, but also the region. Not just that, various aspects of life — say, economic, social, cultural, environmental — which impinge on individuals and the global collectivity at large and which (i.e. those aspects just mentioned) are not part of the traditional concept of security becomes if not security issues themselves, issues relevant to security.

Two problems. First, if it is the same concept of security — Waever thinks it is — that is extended to these realms, then the traditional concept of security with its emphasis on state action usually of a military kind is perhaps not the best way to think about these realms and the issues that concern them. Securitizing these other issues or realms is not really desirable. His recommendation is that we instead try to desecuritize them. Hence the title of the essay! This summary will unfortunately not cover his concrete recommendations.

Second, but if it is not the same concept of security, a new concept of security will have to be articulated. The attempts to broaden security have not done so.

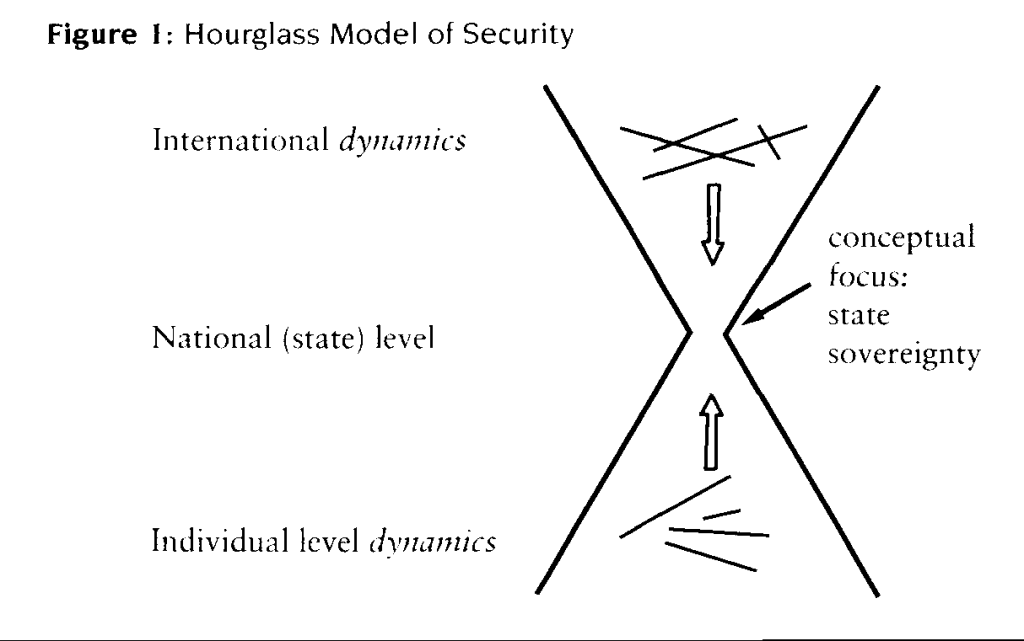

This doesn’t mean that the concept has nothing to do with individuals or with the world. It only means that security “has to be read through the lens of national security.” “Therefore, as indicated in Figure 1, I do not locate security at three levels but at the center of the hourglass image.”

Why do I insist on this?

“[Because] the label ‘security’ has become the indicator of a specific problematique, a specific field of practice. Security is, in historical terms, the field where states threaten each other, challenge each other’s sovereignty, try to impose their will on each other, defend their independence, and so on. Security, moreover, has not been a constant field; it has evolved and, since World War II, has been transformed into a rather coherent and recognizable field. In this process of continuous, gradual transformation, the strong military identification of earlier times has been diminished — it is, in a sense, always there, but more and more often in metaphorical form, as other wars, other challenges — while the images of ‘challenges to sovereignty’ and defense have remained central.”

This insistence is not intended to malign attempts to broaden security. Such attempts are instructive. But if we are interested in contributing something to the debates on security (otherwise also called strategic studies) and national interests, we must not be waylaid by the the word security but be conscious of the concept of security.

What is this concept? It does not have to do with some clearly defined objective or a state of affairs. It has, instead to do with certain typical operations the field of practice of security as defined above. In doing so we are not leaving, at least initially, the traditional realm specified by the state and expressed in terms such traditional notions as national security, threat, sovereignty, etc. But in concentrating on the operations — speech acts and modalities — we might subsequently be able to show how such operations may which characterise the concept of security may be applied to other realms such as the society.

This is another dense argument. Some remarks that might be helpful. When we talk of national security, or talk about the concept of security generally, we tend to think of a state of security which must be attained. [“State” here means a situation as in “My mind was in a peaceful state”. The connection between “state” in this sense and “state” as in “the Indian state” or “nation-states” is not accidental.] The nation must be secure, or secured, we say. This is the idea of security as an objective or a state of affairs which must be attained.

But Waever says that he will articulate security in terms of certain typical operations which are certain speech-acts and modalities. What these are we do not know just yet. But this much is clear: the concept of security no longer designates an objective or a state of affairs. It will instead refer to certain activities. It has to do with what people — scholars, politicians, military generals, and so on — do rather than what they aim at.

There are a number of philosophical notions here — speech-acts, states of affairs [otherwise known as “facts”], and language games (below) — which might be useful to get hold of. I shall comment on speech-acts and language games.

“To start … from being secure in the everyday sense means that we end up approaching security policy from the outside, that is, via another language game. My premise here is, therefore, that we can identify a specific field of social interaction, with a specific set of actions and codes, known by a set of agents as the security field.”

Waever uses the word “game” a number of times in subsequent passages. The idea of “games” is not meant to indicate frivolity or superficiality, as if what is at issue is merely or just a game, something unimportant. The crucial insight here is the idea that games are played with certain rules which are relatively stable and generally accepted. Without such stability and agreement, no game can be played! But these are not rules that are given to us for all time. These rules do not exist out there. There is no such thing as the game with the ultimate set of rules. Rather these rules are rules we make, and therefore rules that we might change, slowly or radically. We might sometimes even choose to completely ignore them. This is the sense in which we must understand his invocation of “games”.

Specifically, the notion of language games comes from Ludwig Wittgenstein. This is a very important notion that would reward further exploration. The remarks about games hold here as well. What I must add though is that for Wittgenstein, what is even more important is the “complicated network of similarities overlapping and criss-crossing: sometimes overall similarities, sometimes similarities of detail”.

“Consider for example the proceedings that we call “games”. I mean board-games, card-games, ball-games, Olympic games, and so on. What is common to them all?—Don’t say: “There must be something common, or they would not be called ‘games’ ”—but look and see whether there is anything common to all.—For if you look at them you will not see something that is common to all, but similarities, relationships, and a whole series of them at that.” (Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, §66)

WIttgenstein calls these similarities and relationships “family-resemblances”.

Additionally, language here doesn’t refer to any specific language. It is a very general term that would capture all symbolic systems through which humans communicate — ancient Greek, French, C++, sign language, calculus notation. It can also mean a specific system employed by, say siblings or carpenters, which is different from that used by academics in a centre for political studies or cricketers of Australia. In all these “forms of life” as Wittgenstein calls them, a certain language game specific to that form of life is played.

Waever’s invocation of a language game is meant to mark off a certain area within which a certain words and phrases — a certain language as we say — is used to convey certain ideas effectively. When we use the word security in our day to day conversation, it means a certain thing (or certain things) to us. What that means to us and how it is understood is bound up with the language game that we play in a form of life that might be called daily life. It is a language game in which we use certain terms like security of life and economic security. It is also a language game in which we don’t use certain terms at all — terms like referent of security or the security problematique. Such terms we reserve for a different language game played in a different form of life that might be called security studies. In this form of life security means quite something else.

Waever’s complaint is that what those before him has done is to take security from the first language game and applied the connotations of security from this language game to the study of security in the second language game. This is problematic on many different levels. To meniton one, just as the rules of one game doesn’t make sense when applied to another game, so with the use of the term security. No wonder there is confusion.

The alternative route to widening the concept of security is along the threats axis, i.e. by looking at threats other than military ones. Here, and this in opposition to the strategy of widening the referents (see above), it is possible to retain the specific characteristics of the security problems: urgency, involvement of state power, sovereignty. For instance, the state can makes its own choices and resort to whatever means it can — and these need not be military ones — whether based on expediency, effectiveness, or even availability, to confront whatever threats it encounters in whatever sector. These measures (of security) are separate from the objectives (of security).

What would make such means those of security? Is it down the swiftness and the unfairness which generally characterise military aggression such that the existence of the political order becomes endangered? This is what Barry Buzan seems to be claiming. If some other sector, say the economic, poses the same danger to the political order, then it will become a security issue.

because the use of force can wreak major undesired changes very swiftly, military threats have normally been accorded the highest priority in national security concerns. Military action can wreck the work of centuries in the political, economic and social sectors, and as such stimulates not only a powerful concern to protect achievements in these sectors, but also a sense of outrage at unfair play.

Buzan, People, States, and Fear, 1983, p. 75.

“Threats seen as relevant are, for the most part, those that effect the self-determination and sovereignty of the unit. Survival might sound overly dramatic but it is, in fact, the survival of the unit as a basic political unit — a sovereign state — that is the key. …With the approach I have suggested here, even if challenges can operate on the different components of the state, they must still pass through one focus: Do the challenges determine whether the state is to be or not to be?”

This will be obvious to many for the benefit of the minority, Waever is here quoting Shakespeare’s Hamlet: To be or not to be, that is the question.

The logic here is simple. It is all well and good to talk about this or that aspect of security but the question of existence of the state — the question of whether the state is to be or not to be — must be addressed first. And if there are issues that impinge on this question, they have to be addressed. Only then can other questions be raised, for if there is no state, there would be no point in raising them. This is expressed most clearly perhaps in Clausewitz. For him, “although politics has to be prior to military, the logic of war — the ziel of war, victory — replaces the logic of politics — the specific zweck. To enter a war is a political decision, but once in, one has to play according to the grammar of war, not politics, which would mean playing less well and losing the political aim, as well.”

Force … is thus the means of war; to impose our will on the enemy is its object [Zweck]. To secure that object [Zweck] we must render the enemy powerless; and that, in theory, is the true aim [Ziel] of warfare. That aim takes the place of the object, discarding it as something not actually part of war itself.

Clausewitz, On War [1832], Chapter 1, Section 2.

What is important to note here is that it is not the use of military means that characterise war. The basic character of war is as “an unconstrained situation, in which the combatants each try to function at maximum efficiency in relation to a clearly defined aim”. It is a historical fact that military means have been associated with war. But the connection between military means and war is just that, historical. It is not a logical connection. Or in other words it is not the use of military means that characterise war.

“War, then, is ‘an act of violence intended to compel our opponent to fulfil our will’ and, therefore, ‘War, insofar as it is a social act, presupposes the conflicting wills of politically organized collectivities.’ … Nonetheless, this struggle can take place in spheres other than the military one; the priority of military means is a contingent, technical feature. Consequently, the logic of war — of challenge-resistance(defense)-escalation- recognition/defeat — could be replayed metaphorically and extended to other sectors. When this happens, however, the structure of the game is still derived from the most classical of classical cases: war.”

From Alternative Security to Security, the Speech Act

“Reading the theoretical literature on security, one is often left without a good answer to a simple question: What really makes something a security problem? As I have suggested above, security problems are developments that threaten the sovereignty or independence of a state in a particularly rapid or dramatic fashion, and deprive it of the capacity to manage by itself. This, in turn, undercuts the political order. Such a threat must therefore be met with the mobilization of the maximum effort.”

“Operationally, however, this means: In naming a certain development a security problem, the ‘state’ can claim a special right, one that will, in the final instance, always be defined by the state and its elites. Trying to press the kind of unwanted fundamental political change on a ruling elite is similar to playing a game in which one’s opponent can change the rules at any time s/he likes. Power holders can always try to use the instrument of securitization of an issue to gain control over it. By definition, something is a security problem when the elites declare it to be so.”

What then is security? Security is a speech act. Specifically, when the term security is used, it does not refer to anything. When we use the term apple, it refers to something, some apple regardless of whether it is real or imaginary, ripe or raw, green or red, etc. But not with security. Here, the utterance itself is the act. “By uttering ‘security,’ a state-representative moves a particular development into a specific area, and thereby claims a special right to use whatever means are necessary to block it.”

Here, Waever is drawing on J. L. Austin and clarifies in a footnote that security is an illocutionary act. I quote Austin:

“To say something is in the full normal sense to do something — which includes the utterance of certain noises, the utterance of certain words in a certain construction, and the utterance or them with a certain ‘meaning’ in the favourite philosophical sense of that word, i.e. with a certain sense and with a certain reference. …The act of ‘saying something’ in this full normal sense I call, i.e. dub, the performance of a locutionary act. …

To perform a locutionary act is in general, we may say, also and eo ipso to perform an illocutionary act, as I propose to call it. To determine what illocutionary act is so performed we must determine in what way we are using the locution: asking or answering a question; giving some information or an assurance or a warning; announcing a verdict or an intention; pronouncing sentence; making an appointment or an appeal or a criticism; making an identification or giving a description; and the numerous like. …

There is yet a further sense in which to perform a locutionary act, and therein an illocutionary act, may also be to perform an act of another kind. Saying something will often, or even normally, produce certain consequential effects upon the feelings, thoughts, or actions of the audience, or of the speaker, or of other persons: and it may be done with the design, intention, or purpose of producing them; … We shall call the performance of an act of this kind the performance of a perlocutionary act.” (How to do Things with Words, 1962, pp. 94–101)

In short, as explained here, “locution is the collective meaning contained within the words of an utterance; illocution is what a speaker intends to have come about as a result of the utterance; and perlocution is what actually results from an utterance.”

The implication here is the the primarity reality is the act, the utterance, and not something that is pre-given. Additionally, this narrows the field or reach of “security” only to those to which the security act, i.e. the utterance of security, is applied. This means that a problem would become a security issue only when it is defined as such by the power holders.

To critique security, as is usually done, in terms of elite or class interests, implying that authentic security lies elsewhere, i.e. with the masses or the people, is simply wrong. These attempts have failed. “Security is articulated only from a specific place, in an institutional voice; by elites.”

Another assumption underlying traditional analyses whether conservative or critical is that security is a positive value to be maximised. The idea being that more security is better. Implying that insecurity is the absence of security and thus a bad situation to be in. But security and insecurity are not binaries. “‘Security’ signifies a situation marked by the presence of a security problem and some measure taken in response. Insecurity is a situation with a security problem and no response. Both conditions share the security problematique.”

“When there is no security problem, we do not conceptualize our situation in terms of security; instead, security is simply an irrelevant concern. …[And] if one has such complete security, one does not label it ‘security.’ It therefore never appears. Consequently, transcending a security problem by politicizing it cannot happen through thematization in security terms, only away from such terms.

This idea, that we cannot transcend security issues thinking through them but by thinking away from them, i.e. that we cannot resolve our issues by securitizing more and more issues but by de-securitizing them, is explored in further sections. Sections which I will not summarize.

“Viewing the security debate at present, one often gets the impression of the object playing around with the subjects, the field toying with the researchers. The problematique itself locks people into talking in terms of ‘security,’ and this reinforces the hold of security on our thinking, even if our approach is a critical one. We do not find much work aimed at de-securitizing politics which, I suspect, would be more effective than securitizing problems.”

************************************

References/ Further Reading

Barry Buzan, People, States, and Fear: The National Security Problem in International Relations (Brighton: Wheatsheaf Books, 1983).

Carl von Clausewitz, On War, trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret, abridged with an introduction and notes by Beatrice Heuser, Oxford World’s Classics (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006).

Carl von Clausewitz, Vom Kriege, Militärische Klassiker (Berlin, 1883).

J. L. Austin, How to Do Things with Words (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962).

Jessica Tuchman Mathews, “Redefining Security,” Foreign Affairs 68, no. 2 (1989): 162–77, https://doi.org/10.2307/20043906.

Johan Galtung, “Twenty-Five Years of Peace Research: Ten Challenges and Some Responses,” Journal of Peace Research 22, no. 2 (June 1985): 141–58, https://doi.org/10.1177/002234338502200205.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, trans. G. E. M. Anscombe (New York: Macmillan, 1963). [Includes the German as well]

Richard H. Ullman, “Redefining Security,” International Security 8, no. 1 (1983): 129–53.

You must be logged in to post a comment.